This project re-examines the dynamics of economic inequality in Thailand from 1975. The main motivation lies in the lack of information on the richest citizens in household surveys, which can lead to a significant underestimation of the inequality level and to an inaccurate representation of the historical trend.

To deal with micro- and macro-level data gaps, administrative data (tax data in this case) and national accounts are utilised for a more consistent distributional series.

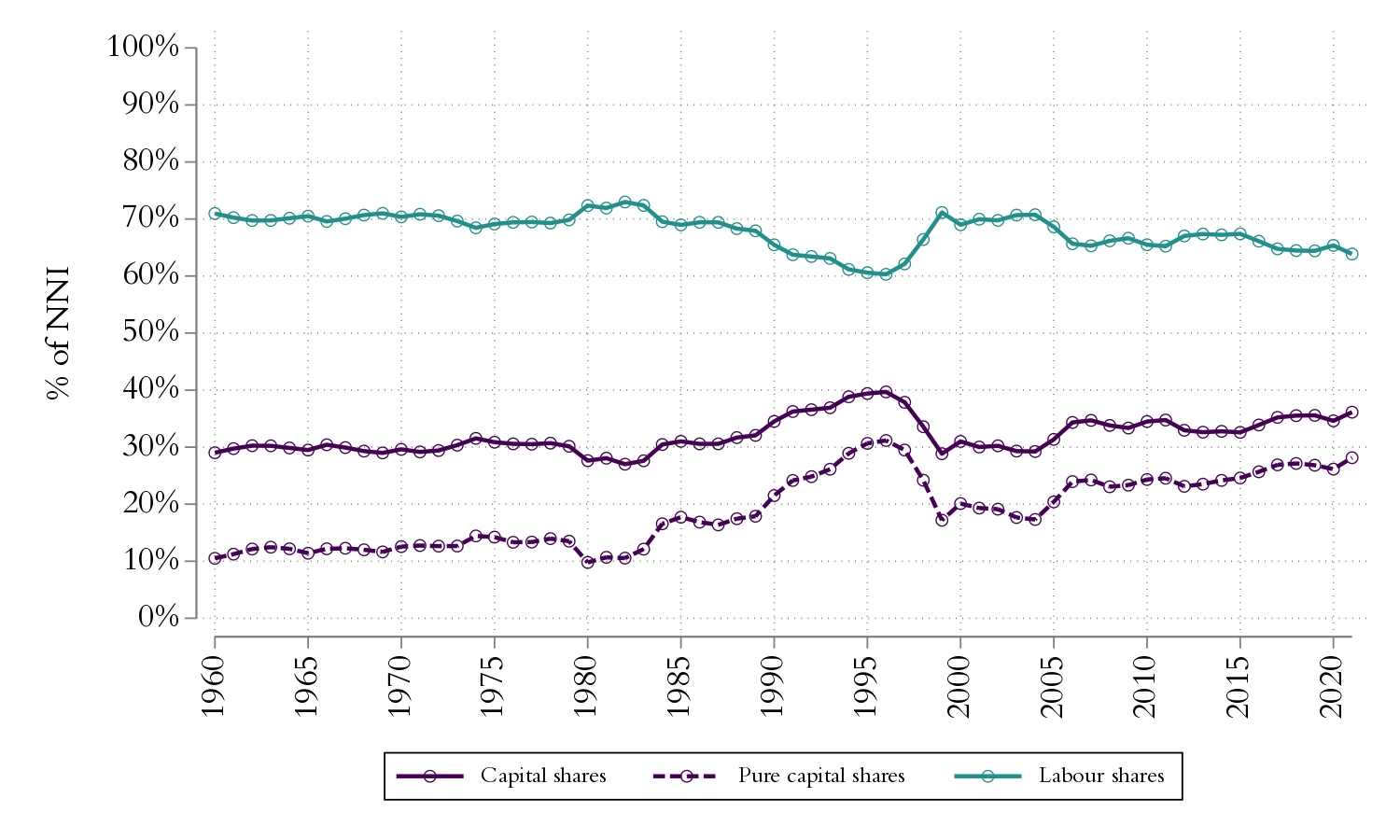

Capital and labour shares in Thailand, 1960-2019. Data from author based on the National Accounts (NESDC) and Jetin (2012)

References

Technical Reports

2019

-

Extreme Inequality, Democratisation and Class Struggles in Thailand

Thanasak Jenmana, and Amory Gethin

2019

Thailand is finally set to have a general election on 24 March 2019 after five years of military government and a long period of political uncertainty. In this note, we argue that a main source of political instability is brought by Thai- land’s extreme levels of income, wealth and regional inequalities, as well as by the rising politicisation of class conflicts around redistributive issues which followed the Asian Financial Crisis. New historical series on inequality in Thailand point to very high levels of income concentration. In 2016, top 10% earners received more than half of the national income, which is higher than what can be observed in most world regions. The social policies implemented by successive democratic govern- ments since the 2000s have been successful at promoting a fairer distribution of labour earnings. Inequalities remain high, however, due to the strong concentration of wealth and capital incomes, which are not addressed by existing fiscal policies. The post-1997 party politics successfully put an end to a long period of ris- ing income disparities. Most importantly, they have been associated with the emergence of class cleavages visible in voting behaviours and party identifica- tion. These are conflicts opposing the established middle class and elites, who lost their relative economic and political power, to the poor and the emerging middle class who have benefited from a new and fairer economic era and put strong values on general elections.

2018

-

Democratisation and the Emergence of Class Conflict: Income Inequality in Thailand, 2001-2016

Thanasak Jenmana

Nov 2018

This paper re-examines the dynamics of income inequality in Thailand between 2001 and 2016. The main motivation lies in the lack of information on the richest citizens in household surveys, which can lead to a significant underestimation of the inequality level and to an inaccurate representation of the historical trend. We combined household surveys, fiscal data, and national accounts to create a more consistent inequality series. Our results indicate that income inequality is much higher than what past surveys have suggested, specificallywhen looking at the reduction in inequality, which turns to be much more conservative. The top 10% income share went from 56% of national income in 2001 to 53% in 2016, and the bottom 50% share increased from 9% to 13%. The Gini coefficient decreased by 0.06, reaching 0.62 in 2016. The income of each generalised percentiles are also decomposed into labour and capital income, in which we observe the higher importance of capital income in the top 1% only. These observed dynamics can be put into perspective using recent political conflicts in Thailand, where a strong anti-democratic sentiment has risen within the middle and upper social classes. In line with recent works, we argue that the shifting economic power towards the bottom 50% led to the strong reaction from the middle class, who had benefited more economically during the second half of the 19th century. Using CSES data, it is briefly shown that there has been a rise of class cleavages in Thai politics from 2001 and on, reflecting these patterns.